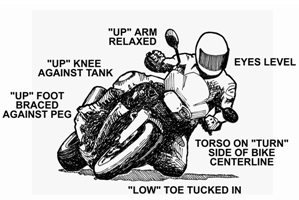

You don't have to hang way off the bike in every curve to achieve

better cornering control. Just sliding from one side of the saddle

to the other will have an effect. But if you do want to hang off

more aggressively, here are some pointers:

1. Hang off early

Shift your weight before you lean the bike into the curve. Get

your entire upper torso to the "turn" side of the bike centerline

two or three seconds before your turn-in point. You may have to hold

some pressure on the "up" grip to keep the bike from turning until

you're ready. At the turn-in point, simply relax your steering input

to allow the bike to lean over.

2. Get tucked in

Wedge your "up" knee against the tank to prevent sliding off too

far. Brace your "up" leg against the footpeg. Tuck your "down" toe

in to prevent snagging it on the ground. You don't want to get your

foot caught between the peg and the pavement.

3. Eyes level.

Tilt your head to keep your eyes level with the horizon. Level

eyes provide a more stable view of the road, and that helps you

understand the shape of the curve and predict where the bike is

headed.

4. Countersteer.

With the bike leaned over, press the grips toward the direction

you want to go. In a left turn, pressing both grips toward the left

will lean the bike over farther. Or, as Total Control author Lee

Parks suggests, steer with one hand. In a right-hander, steer with

your right hand. In a left-hander, steer with your left hand.

Below: If you decide to add "hanging off" to your set of

riding skills, learn to do it right.

Eyes Up

Whatever the bike you're riding, or however aggressively you are

riding it, it's very important to get your eyes up. At a road speed

of only 55 mph, you're covering almost 80 feet per second. Even if

you notice a hazard and try to take some evasive action, it takes

time to make it happen. A reaction time of one second is very quick.

Even if you are able to react within one second, you will have

covered 80 feet before anything happens. In other words, at 55 mph,

that next 80 feet ahead of the bike is history. The message is:

there's no point in looking down at the pavement 50 or 60 feet in

front of the bike.

Looking farther ahead gives you more time to react to what you

see. So, get your eyes up, and scrutinize what's happening as far

down the road as you can see details.

Point Your Nose

We tend to point the bike where we are looking. And we also tend

to point the bike in the direction our face is headed. So, it helps

to actually turn your head and point your nose where you want the

bike to go. As you lean the bike into a turn, keep your eyes level,

and look around the corner as far as you can see. But resist the

urge to stare at the painted lines. Instead, imagine your line

through the turn, and keep your nose pointed where you want the bike

to go.

At right: There's no point in looking down in front of the

bike, because whatever happens within the next second or two is

already history. Get your eyes up, scrutinize the road as far ahead

as you can see, and point your nose at the line you want the bike to

follow.

Crash Padding

If you want to avoid running into something, you have to be able

to either swerve around it, or stop short of it. Either way, you

need to be able to control the bike within the road you can see. The

shorter your sight distance, the more you are depending upon luck

rather than skill.

One of the big challenges of very twisty roads with tight bends

is that the view ahead is frequently limited. Even if you are very

skilled and your reaction times are very quick, it's easy to find

yourself going way too fast to be able to respond to a hazard that appears

suddenly, halfway around the turn. You may be in good control of the

bike, but not in control of the situation. The chances are that

sooner or later some situation will exceed your skill and knowledge

levels.

For that reason, clever riders wear impact and abrasion resistant

riding gear. The message is: when you get your turn to crash, you'll

be sliding down the pavement in whatever you chose to put on before

the ride. If your riding gear is comfortable and functional, you're

more likely to wear it "ATGATT". (All The Gear, All The Time).

David Hough

is a long-time motorcyclist and journalist. His work has appeared in numerous motorcycle publications, but he is best known for the monthly skills series "

Proficient Motorcycling

" in Motorcycle Consumer News, which has been honored by special awards from the Motorcycle Safety Foundation. Selected columns were edited into

two books

Proficient Motorcycling

and

More Proficient Motorcycling

, both published by Bowtie Press. He is also the author of

Driving A Sidecar Outfit and a pocket riding skills handbook,Street Strategies

.